A main limitation of the present study relates to its exploratory nature and the statistical robustness of the findings. First, only one author conducted the data extraction and coding, meaning there could be a degree of bias and risk of errors in the process. However, a protocol was put in place to guide the project and frequent support and supervision was given with the second author. Some caution is also warranted considering the statistical issues of non-normality, relatively high levels of multicollinearity and chances of random error when dealing with 15 to 17 factors within a relatively small dataset. Still, the relation between author countries and included non-English studies was consistent for all models, except for the bootstrapped ones, which added some credibility to the results, supported by the qualitative data. Unfortunately, the results are somewhat confounded by the 35 systematic reviews—accounting for 17.9% of the total Campbell authorship —that did not report exhaustively on the institutional affiliation of all review authors.

The Cochrane Handbook acknowledges the risk of bias in reviews containing exclusively English language studies and somewhat vaguely recommends 'case-by-case' decisions concerning the inclusion of non-English studies . Similarly, the methodological guidelines for Campbell Collaboration reviews warn against the risk of language bias and encourages authors not to restrict by language . The lack of concrete advice and guidelines is problematic because non-English studies have been shown to be more cumbersome for researchers to identify than English language studies.

Research databases, for example, are less rigorous in their inclusion and indexing of non-English studies . Searching specialised non-English language databases using search terms in the appropriate language might alleviate this problem , but researchers are still limited by their own language skills or their ability to pay for the services of professional translators. For these reasons, reviewers commonly report that it is costly and time-consuming to include non-English studies and use this to justify a priori exclusion . Noteworthy for the present study, the role of non-English studies appears to be largely unassessed within the social sciences where publication channels are more prone to publication biases .

Studies published in languages other than English are often neglected when research teams conduct systematic reviews. Literature on how to deal with non-English studies when conducting reviews have focused on the importance of including such studies, while less attention has been paid to the practical challenges of locating and assessing relevant non-English studies. We investigated the factors which might predict the inclusion of non-English studies in systematic reviews in the social sciences, to better understand how, when and why these are included/excluded. We investigated the factors that might predict the inclusion of studies that are in languages other than English in systematic reviews, particularly in the social sciences. We analysed all 123 systematic reviews published by the Campbell Collaboration, categorising each by its language inclusiveness.

We also sought additional data from review authors and received responses from around one third of our sample. We found few and smaller differences when comparing the three review categories , for example in relation to the number of data sources sought. In practice, however, the number of data sources might be less relevant than which (non-English language specialised) data sources a review team searched. Perhaps the clear dominance of individual researchers based in English-speaking countries and review teams consisting only of team members in these countries reflects a partiality among publication channels for studies in English. Additionally, if the low prevalence of non-English search terms is a proxy for the general rigour with which non-English studies have been pursued, the factor that we identified (authors' working countries) might not be the most effective.

Factors such as the number of search-term languages might be more important in practice if they were applied more often. This speculation is not supported by our statistical models, which did not identify language as being of significant importance. However, the data on author languages was to some degree unreliable as questionnaire respondents expressed uncertainty about languages spoken by their co-authors.

Further, the questionnaire only covered 47 of the 123 review teams, which lowers its statistical power to identify a real relationship, if one exists. The statistical power of another language variable identified by earlier research —the application of non-English search term in the literature search process—is also low due to the few reviews that applied non-English search terms. We therefore cannot confirm the importance of language in accessing non-English studies, nor do we have reason to reject the importance of language diversity. Results of the author questionnaire suggested that the most obvious challenges to include non-English studies were resource constraints and, somewhat linked to this, the reliance of research teams on their own internal language skills. In this light, Fig.1 illustrates that review teams may expect an overwhelming number of studies to screen and full-text assess when seeking to include non-English studies. To counter this challenge, we suggest two options that could lower the work load burden for C2 review teams and improve the review quality.

First, teams might benefit from putting more effort into improving the specificity of their research questions and search strategies. Our regression analyses indicated a negative relationship between the number of studies screened and the inclusion of non-English studies, as well as a positive relationship between the number of studies included and the inclusion of non-English studies. Indeed, Fig.1 does illustrate that LOE-inclusive reviews succeed in including more relevant studies disregarding publication language than LOE-open reviews, while screening substantially fewer studies.

It might also be that the range of author countries is a proxy for knowledge about and access to more diverse or specific publication channels that facilitate the inclusion of non-English studies. Finally, there might be a degree of selection effect operating, whereby international review teams pick research topics with more global relevance and therefore a higher prevalence of non-English studies. Among the 123 reviews in our study, 108 did not exclude non-English studies a priori, and of those who did, few justified their reasons to do so.

The relatively low prevalence of non-English studies in our sample of reviews might be somewhat underestimated by our data extraction approach, counting non-English titles in the study inclusion list. Assuming that this is not the case, the low prevalence might indicate that relevant non-English studies were not available or that the review teams failed to identify these studies. We did not assess whether relevant non-English studies had been overlooked or, if located, were excluded due to risk of bias. Overall, however, the infrequent number of non-English studies does leave some room for C2 to convincingly develop a 'world-library of systematic reviews' . At the moment, we cannot tell to which degree the results can be extrapolated from our sample of Campbell reviews to the wider population of reviews.

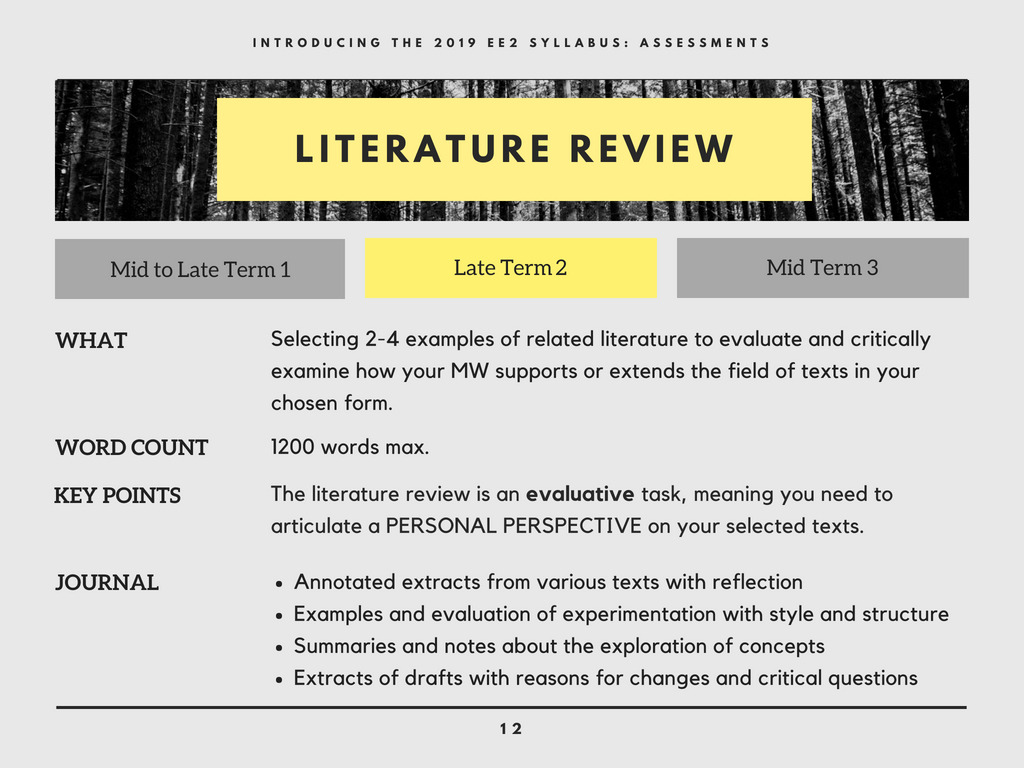

What Is Literature Review In English A literature review is an overview of the previously published works on a specific topic. The term can refer to a full scholarly paper or a section of a scholarly work such as a book, or an article. Either way, a literature review is supposed to provide the researcher/author and the audiences with a general image of the existing knowledge on the topic under question. A good literature review can ensure that a proper research question has been asked and a proper theoretical framework and/or research methodology have been chosen. To be precise, a literature review serves to situate the current study within the body of the relevant literature and to provide context for the reader. In such case, the review usually precedes the methodology and results sections of the work.

Reviews which included non-English studies were more likely to be produced by review teams comprised of members working across different countries and languages. For example, international review teams may have easier, perhaps informal, access to and/or knowledge about a more diverse set of language resources and publication channels than teams working within the same country. Or there might be a degree of selection effect in play, whereby international review teams pick research topics with more global relevance and therefore a higher prevalence of non-English studies. Having extracted the majority of data from the C2 reviews, we found that some relevant factors were likely underreported to assess their importance. We also asked respondents what they perceived to be the barriers and facilitators of including non-English studies. These free-text box inputs from the author questionnaire were coded iteratively and aimed to identify the challenges that review teams experience when considering, or actually including, non-English studies in Campbell reviews.

This study sought to identify and explore factors that might predict the inclusion in or exclusion from systematic reviews of studies that are in languages other than English. It also sought to extend the investigation of non-English study inclusion from the health sciences to the social sciences. Literature refers to a collection of published information/materials on a particular area of research or topic, such as books and journal articles of academic value. However, your literature review does not need to be inclusive of every article and book that has been written on your topic because that will be too broad. Rather, it should include the key sources related to the main debates, trends and gaps in your research area.

If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper's investigation.

Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers. This study has highlighted some of the remaining questions around language inclusiveness in systematic reviews and the unique challenges involved in locating and assessing available non-English studies. In light of these issues, we recommend replicating our study using a wider range of reviews, for example using the Cochrane Library as a sample. Such efforts are crucial if the evidence-based movement is to succeed in becoming a global movement of people aiming to build a world library of systematic reviews. Unsurprisingly, authors commonly pointed to issues of cost, time and funding as crucial for the inclusion of non-English studies, as well as lack of language resources . 'Language resources' here refers to people or services external to the review team (e.g. professional and volunteer translators, software translation tools and English abstracts).

'Language skills'—the language competencies within the review teams (e.g. multilingual authors and affiliated staff)—was not experienced as a barrier, nor a facilitator, as often as language resources, but was still pointed to as the third most common barrier. Slightly more often than language skills, authors pointed to the need for training in and guidelines on how to deal with non-English studies and access to non-English specialised databases as important facilitators. Issues of bias and methodological quality were mentioned, although infrequently.

You've decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you've just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale's portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980's. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century.

Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel. In addition, this type of literature review is usually much longer than the literature review introducing a study. At the end of the review is a conclusion that once again explicitly ties all of these works together to show how this analysis is itself a contribution to the literature. While it is not necessary to include the terms "Literature Review" or "Review of the Literature" in the title, many literature reviews do indicate the type of article in their title. Whether or not that is necessary or appropriate can also depend on the specific author instructions of the target journal.

Have a look at this article for more input on how to compile a stand-alone review article that is insightful and helpful for other researchers in your field. To counter non-normal data distribution, all models were bootstrapped with 1000 samples. A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized.

This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period.

Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not. Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word "review" in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database.

The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read are also excellent entry points into your own research. A meta-analysis is typically a systematic review using statistical methods to effectively combine the data used on all selected studies to produce a more reliable result. A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis).

It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries. Finally, after you have finished drafting your literature review, be sure toreceive proofreading and language editing for your academic work. A competent proofread who understands academic writing conventions and the specific style guides used by academic journals will ensure that your paper is ready for publication in your target journal. Second, more review teams could consider explicitly restricting their reviews to English language publications and state, as well as justify, this limitation, e.g. in abstracts, research questions, objectives and eligibility criteria.

Pragmatically restricting reviews to English publications is legitimate but should be clearly acknowledged and the limitations in findings and their relevance should then be properly discussed by review teams. Future C2 guidelines could address these issues more clearly as called for by some of our questionnaire respondents. Abstracts were assessed to determine if they included research questions that stated a geographical focus on predominantly English-speaking countries (i.e. USA, UK, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand), which could lead to categorising the review as EL-justified.

Therefore, we also extracted any information about geographical limitations that were stated in the research objectives, as a way to identify when reviews were EL-justified. Our findings may indicate a connection between the limited inclusion of non-English studies and a lack of resources, which forces review teams to rely on their limited language skills rather than the support of professional translators. If unaddressed, review teams risk ignoring key data and introduce bias in otherwise high-quality reviews. However, the validity and interpretation of our findings should be further assessed if we are to tackle the challenges of dealing with non-English studies. In a larger piece of written work, such as a dissertation or project, a literature review is usually one of the first tasks carried out after deciding on a topic.

Reading combined with critical analysis can help to refine a topic and frame research questions. A literature review establishes familiarity with and understanding of current research in a particular field before carrying out a new investigation. Conducting a literature review should enable you to find out what research has already been done and identify what is unknown within your topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research. The more reviews one reads in the context of an article, the better one understands the specific demands for literature in a given study.

Your hypothesis, argument, or guiding concept is the "golden thread" that will ultimately tie the works together and provide readers with specific insights they didn't have before reading your literature review. This is not usually a linear process—authors often go back and check the literature while reformulating their ideas or making adjustments to their study. Sometimes new findings are published before a study is completed and need to be incorporated in the current work. This also means you will not be writing the literature review at any one time, but constantly working on it before, during, and after your study is complete.

These literature reviews are generally a bit broader in scope and can extend further back in time. This means that sometimes a scientific literature review can be highly theoretical, in addition to focusing on specific methods and outcomes of previous studies. In addition, all of its sections refer to the literature rather than detailing a current study.

The literature review published as its own article presents and analyzes as many of the important texts in an area of study as possible to provide background information and context for a current area of research or a study. Stand-alone reviews are an excellent resource for researchers when they are first searching for the most relevant information on an area of study. The literature review found at the beginning of a journal article is used to introduce research related to the specific study and is found in the Introduction section, usually near the end. It is shorter than a stand-alone review because it must limit its scope to very specific studies and theories that are directly relevant to this study. Its purpose is to set research precedence and provide support for the study's theory, methods, results, and/or conclusions.

Not all research articles contain an explicit review of the literature, but many do, whether it is a discrete section or indistinguishable from the rest of the Introduction. Three exploratory multivariate models were tested with the software, SPSS Statistics 25 for Windows, to identify factors that correlate with the number of included non-English studies in the Campbell reviews. Due to the explorative nature of the study and the low statistical power from the small sample, we accepted significant associations at a p value of 0.10 when running regressions to identify possible associations.